Inside Track: Kendrick Lamar’s To Pimp A Butterfly Secrets Of The Mix Engineers: Derek Ali

P2P | 20 August 2015 | 2.7 MB

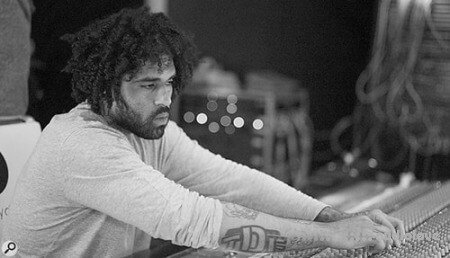

“I’m 25, I have been doing this for only seven years, and I’m still learning. I just feel blessed to be here. But the response to Kendrick’s album has been crazy, and that people also notice the sound of the album, and therefore my work, is just amazing!”

Speaking from his Los Angeles home, Derek Ali still sounds a bit overcome by the success of Kendrick Lamar’s third album, To Pimp A Butterfly, which topped the UK and US charts and has enjoyed almost unanimous critical praise. A sprawling, intense piece of work, with 16 tracks clocking in at nearly 80 minutes, it is full of original, played and programmed music as well as samples, with the most important influences being jazz and the funk and soul music of the ’70s. Many of the tracks are stream-of-consciousness collages, which unexpectedly change musical styles, moods or tempi. The album took more than three years to make, involving multiple studios in LA, New York, Washington and St Louis, as well as Lamar’s tour bus.

Keeping everything together were relative rookie Derek ‘MixedbyAli’ Ali and Lamar himself. The two have been working together for Ali’s entire studio career: he also engineered and mixed Lamar’s first album Section.80 (2011) as well as Lamar’s commercial breakthrough and major-label debut Good Kid, M.A.A.D City (2012). Ali’s rise to the very top of the American engineering and mixing world in the amazingly short time span of seven years is, by any standard, a remarkable achievement, especially as he grew up in extreme poverty, in the Gardena neighbourhood of LA.

“I never had the patience to actually learn to play an instrument or make a beat, or something like that,” recalls Ali. “But I was a curious kid, and back in my neighbourhood there were these Nextel cell phones for which people wanted custom ringtones. Growing up there was very, very hard, but I managed to buy an Audio-Technica 2025 microphone for 100 bucks and an M-Audio Solo interface and I used them to record into Fruity Loops and Cool Edit Pro in which I created personal ringtones for people. The fact that I could record somebody’s vocal and could manipulate it in all sorts of ways really intrigued me, so I started to explore engineering. The more I got into it, the more I wanted to know how the professionals did it. I did a lot of research. I tried to learn everything I could about recording, mixing and mastering techniques. Being self-taught is a great teacher. I often sat for 12-18 hours a day to hone my skills.”

Becoming Top Dawg

To Pimp A Butterfly sounds like it had a dyed-in-the-wool engineer and mixer at the controls, not someone who very modestly claims that he’s still learning his craft. What’s more, despite his home-schooled audio background, Ali prefers to mix in the analogue domain rather than ‘in the box’.

“I didn’t really have one big break, it all came through my work with Kendrick,” explains Ali. “We’ve been working together for over seven years, and as his career built, people wanted to know who was doing all these effects on his vocals. So I was gaining people’s interest through their ears. When Kendrick signed with Top Dawg Entertainment (TDE), we had our own makeshift studio at the house of the company’s CEO, which was just Pro Tools with an Mbox, a PreSonus mic pre, and a cheap little mic. I became TDE’s in-house engineer and we recorded at least 12 albums for TDE at this studio! Kendrick and I later started working at Dr Dre’s studio. He is one of the greatest, and he was super hands-on with Kendrick’s M.A.A.D album.

“But Kendrick has his own sound, so when it was time to mix that album, Kendrick said that he wanted me to mix it. Dre appreciated that, because he liked a young guy who wanted to learn the art of engineering and mixing, instead of wanting to become a producer or a rapper. So he took me under his wing, and showed me a lot of techniques that you can’t learn in books and that he developed over the years, and that I then made my own. I went from Pro Tools LE with an Mbox to an SSL 4000 overnight, and just watching Dre work and how he got the drums and kick to smack and so on was an inspiration. Since then I’ve always used a board when recording and mixing.

“People look at me as if I am crazy, wondering whether desk does not take longer and eats up the budget! But I don’t care what anybody says: you can’t get that analogue sound in the box, period. You simply cannot recreate that sound with plug-ins. Second, working on the desk and with outboard gives you a hands-on feeling with the music. Kendrick’s songs have a lot of movement and changes in them, and when I am working with faders I feel like I am touching the music and am part of it. I don’t like looking at a screen for hours. It makes me feel like I am not free. I want to feel free when I am working. I want to be like an artist in a booth who can move his hands and feel free and express himself. I don’t want to feel like I am editing a movie.

“It may cost more to use a desk and outboard, but you can’t cheapskate good work. In my experience, when you are sitting in front of a computer, you’re missing out on something. Honestly, when you are looking at a screen, you are looking at numbers. Whereas when you are on a board in analogue, you are working with your ears. In digital you can turn things up or down a specific amount of decibels, or tune this or that frequency. But how useful is that? It is a bit like going to a school for engineering. You can learn many valuable things there, but the one thing that you cannot be taught is how to hear something. Nobody else can teach you your own taste and tell you what number is right. It is just a number. Instead you have to train your ear, you have to learn to notice the different frequencies and sounds, and then let your own taste decide.”

Tom-Tom Club

Kendrick Lamar is, by all accounts, a workaholic, who loves nothing more than spending time in the studio writing and recording. And so work on To Pimp A Butterfly began at the end of 2012, immediately after the release of and promotional tour for M.A.A.D City. Lamar and Ali spent most of their time at No Excuses in LA, with the other studios mentioned in the credits for the album used only very briefly.

“Sometimes Kendrick would do a show somewhere, and after the show he still wants to work, so we go to a local studio,” recalls Ali. “He’s also had a studio in his tour bus ever since we were on tour for the first album. If he didn’t have that, he’d be recording in GarageBand! So we made it easier for him, and set up this studio in the bus, with a simple setup, consisting of a Pro Tools HD rack, two mics, the Sony C800G and a Telefunken U47 and an Avalon mic pre. Nothing crazy, just stuff that allows us to get down ideas. But our main headquarters for the making of the album was Tom-Tom (the nickname for No Excuses Studio), which is owned by Interscope. It has Dre’s former SSL 4000 G+, the last G-series ever built, in 1991. He mixed his album The Chronic (1992) on it and Eminem’s The Slim Shady LP (1999), and lots of other famous albums, so it’s a real classic board in rap history.”

Far more live musicians and fewer samples were used than is normal on a hip-hop album. “The main guys who were there for the entire making of the album were Kendrick, myself and producers Terrace Martin, Rahki, Tae Beast and Sounwave [the latter two are members of the Digi+Phonics production collective, the main in-house producers for TDE]. That was the core personnel, and we were involved from day one until the day we finished the last mix. We consider each other brothers, and Kendrick does not look at this as purely his album. When we were in the studio he talked about it as our album. He brought everybody in and we voted on how things should sound and work. When we played what we were doing to people, many were just dumbfounded and said that they’d never heard anything like this before. For this reason the other producers had to be around and feel the energy and connect with Kendrick’s vision.

“The other producers came in when Kendrick had ideas for working with them, guys like Pharrell, Thundercat and Flying Lotus. Boi-1da is based in Toronto and he was one of the only ones who didn’t come over to the studio. The general working method in hip-hop of the producer sending over some beats didn’t work for this album. There were just a couple of songs on the album that came out of people sending us beats. Like Kendrick found this beat by Knxwledge in his e-mail, and we were like, ‘What’s this?’ It just matched the aesthetic of the album so well, and we used it for the track ‘Momma’. But A&R guys sometimes brought in producers or tracks and we’d just be sitting there looking at each other and going, ‘This has nothing to do with what we’re doing at the moment.’”

Writing In The Head

Although Dr Dre is credited as the executive producer of To Pimp A Butterfly, Ali stresses that it was Lamar’s vision that unified all the album’s disparate ingredients and contributors. “It’s almost crazy watching him, because he knows exactly what he wants. Big names mean nothing to him. He may listen to the way someone sings or plays, and if he likes it, he’ll incorporate that into his project, but in a way that fits his vision. He looks at people’s vocals as instruments. Kendrick knew what he wanted to talk about with regards to the lyrics, and from there it was a matter of piecing the music together, and making that fit with the vocals. He writes in his head, and he’ll hear a beat, or a bass line, or an instrumental or vocal melody, and he’ll build a track from there. Like Thundercat may be playing an amazing bass line in the studio lounge, and Kendrick might be having a conversation with someone else, but a moment later he’ll write something to fit that bass line, and five minutes later he’ll say, ‘Let’s record that.’ With the track ‘i’ he was literally trying to play a guitar to demonstrate what he wanted. He writes all the words, of course, but is also 100 percent involved in the writing of the music.

“We recorded 60 to 80 tracks for this album over the three years, and Kendrick tried many different concepts and approaches. The final direction began to emerge in the last year and a half or so, with most of the tracks written and played from the ground up. There were many live instruments used, and that’s why we had our core team, with guys programming drums, and playing bass, guitars and keyboards, so we could arrange the music in the studio, live. Most songs would start with drums and bass, over which Kendrick would record a rough vocal. After that we’d stack the rest of the musical instruments on top, usually layer by layer. He tends to mumble melodies or harmonies for his roughs on top of the drums and bass, and after we recorded all the music, he’d write the actual lyrics and then he’d record his vocals again. It was kind of a backwards way of working, but it was cool.”

In addition to programmed drums and electronics, the album also features acoustic instruments like violin, trumpet, guitar, double bass, saxophones, clarinet, organ, piano, as well as extensive backing vocals. “Each song had its own sound world and its own process,” explains Ali. “The opening track, ‘Wesley’s Theory’, initially did not have the Boris Gardiner sample, but was produced by Flying Lotus, with Sounwave doing the instruments. ‘King Kunta’ is bass-heavy and influenced by the West Coast hip-hop from DJ Quik, who was big in the gangsta movement of the ’90s, and who had loads of jazz and funk influences in his music. Kendrick really wanted his sound for this song, and he had started with doing a vocal to a beat by DJ Quik. Sounwave then later created a new beat to match Kendrick’s vocals.

“‘For Free?’ was produced by Terrace Martin, who is a jazz player himself, and who arranged the song for a live jazz band. The energy of that session was amazing. I had never seen anything like that ever in my life. It got me into jazz, honestly. Just tuning my ears for his album I’ve been listening to a lot of jazz albums, and I kind of fell in love with it. In fact, this album opened my ears to many different genres of music. I come from a place where there was no jazz; I was raised on gangsta rap.”

All About Feeling

As the main engineer on To Pimp A Butterfly, Ali was responsible for keeping track of everything and organising the material, with the assistance of James Hunt and Matt Schaeffer. According to Ali, he and Lamar work in a very collaborative way, with the artist relying on Ali to supply him with sonic ideas that he then uses for inspiration.

“With Kendrick it’s all about feeling. If it doesn’t feel good, it’s not going to work for him. And what a lot of people don’t realise is that you can alter people’s emotions with certain frequencies and sonic textures. The fact that I can add delays and reverbs and other crazy effects to music or vocals and give them extra emotion is amazing to me. That’s what I do this for. Kendrick understands this, and he may be midway through recording a verse, and he’ll then ask me to try something, like ‘Can you add some flanging, or some panning, or something else crazy?’

“We’ve been working like that for years and it got my ears tuned to all kinds of different effects. When it’s during recording, I tend to do these effects in the box. It might take me a few minutes to set up, but it’s fun. In some ways the engineer-artist relationship is like driving a car, going on a road trip. The artist knows where he wants to go, but it is up to the engineer to take him there.

“The whole recording process was like filling in a check-sheet, and Kendrick always knew what he still had to finish or go back to. Towards the end of the project it became more of a mix-as-you-go situation, because of deadlines, but in general, once all the parts were recorded, and the song was structured and edited and sequenced, it was time to mix. Kendrick and I would have already discussed the direction for each song during the recordings, so for me also it’s just a matter of waiting until all the sounds are in, piecing and editing everything together in Pro Tools, and then I’d wait a day, to give my ears a break, and then it was time to do the final mix.

“We did all the mixes at Tom-Tom. The process was that after my day off I’d lay the mix out over the SSL, and then I’d spend one or two days on the mix. Kendrick and the other guys would be present with me in the room while I was mixing, non-stop. I am blessed to work with them, because they give me freedom to do all this crazy stuff, because they know what I am capable of. They’re not leaning over my back telling me what to do. After the initial one or two days mixing, I’d spend a day living with the mix, listening to it on all sorts of different speakers and in different situations. I’ll listen in my car, on my little home boombox speaker, in all sorts of places where people will be hearing them. Kendrick and I might also be listening to it in my home studio, where I have a Pro Tools rig, and Yamaha NS10s, Neumann and Auratone monitors. We’ll discuss what elements we want to bring out more. But really, most of the mix is done after those first one or two days. After that it’s just a matter of adding a little bit of sugar and spice. I’d come back in the studio the next day, and incorporate any final feedback from the guys, and I’d then print the mix, back to Pro Tools via a Lavry Gold A-D converter, and to half-inch analogue tape, using an Ampex ATR102 machine.”

home page

Speaking from his Los Angeles home, Derek Ali still sounds a bit overcome by the success of Kendrick Lamar’s third album, To Pimp A Butterfly, which topped the UK and US charts and has enjoyed almost unanimous critical praise. A sprawling, intense piece of work, with 16 tracks clocking in at nearly 80 minutes, it is full of original, played and programmed music as well as samples, with the most important influences being jazz and the funk and soul music of the ’70s. Many of the tracks are stream-of-consciousness collages, which unexpectedly change musical styles, moods or tempi. The album took more than three years to make, involving multiple studios in LA, New York, Washington and St Louis, as well as Lamar’s tour bus.

Keeping everything together were relative rookie Derek ‘MixedbyAli’ Ali and Lamar himself. The two have been working together for Ali’s entire studio career: he also engineered and mixed Lamar’s first album Section.80 (2011) as well as Lamar’s commercial breakthrough and major-label debut Good Kid, M.A.A.D City (2012). Ali’s rise to the very top of the American engineering and mixing world in the amazingly short time span of seven years is, by any standard, a remarkable achievement, especially as he grew up in extreme poverty, in the Gardena neighbourhood of LA.

“I never had the patience to actually learn to play an instrument or make a beat, or something like that,” recalls Ali. “But I was a curious kid, and back in my neighbourhood there were these Nextel cell phones for which people wanted custom ringtones. Growing up there was very, very hard, but I managed to buy an Audio-Technica 2025 microphone for 100 bucks and an M-Audio Solo interface and I used them to record into Fruity Loops and Cool Edit Pro in which I created personal ringtones for people. The fact that I could record somebody’s vocal and could manipulate it in all sorts of ways really intrigued me, so I started to explore engineering. The more I got into it, the more I wanted to know how the professionals did it. I did a lot of research. I tried to learn everything I could about recording, mixing and mastering techniques. Being self-taught is a great teacher. I often sat for 12-18 hours a day to hone my skills.”

Becoming Top Dawg

To Pimp A Butterfly sounds like it had a dyed-in-the-wool engineer and mixer at the controls, not someone who very modestly claims that he’s still learning his craft. What’s more, despite his home-schooled audio background, Ali prefers to mix in the analogue domain rather than ‘in the box’.

“I didn’t really have one big break, it all came through my work with Kendrick,” explains Ali. “We’ve been working together for over seven years, and as his career built, people wanted to know who was doing all these effects on his vocals. So I was gaining people’s interest through their ears. When Kendrick signed with Top Dawg Entertainment (TDE), we had our own makeshift studio at the house of the company’s CEO, which was just Pro Tools with an Mbox, a PreSonus mic pre, and a cheap little mic. I became TDE’s in-house engineer and we recorded at least 12 albums for TDE at this studio! Kendrick and I later started working at Dr Dre’s studio. He is one of the greatest, and he was super hands-on with Kendrick’s M.A.A.D album.

“But Kendrick has his own sound, so when it was time to mix that album, Kendrick said that he wanted me to mix it. Dre appreciated that, because he liked a young guy who wanted to learn the art of engineering and mixing, instead of wanting to become a producer or a rapper. So he took me under his wing, and showed me a lot of techniques that you can’t learn in books and that he developed over the years, and that I then made my own. I went from Pro Tools LE with an Mbox to an SSL 4000 overnight, and just watching Dre work and how he got the drums and kick to smack and so on was an inspiration. Since then I’ve always used a board when recording and mixing.

“People look at me as if I am crazy, wondering whether desk does not take longer and eats up the budget! But I don’t care what anybody says: you can’t get that analogue sound in the box, period. You simply cannot recreate that sound with plug-ins. Second, working on the desk and with outboard gives you a hands-on feeling with the music. Kendrick’s songs have a lot of movement and changes in them, and when I am working with faders I feel like I am touching the music and am part of it. I don’t like looking at a screen for hours. It makes me feel like I am not free. I want to feel free when I am working. I want to be like an artist in a booth who can move his hands and feel free and express himself. I don’t want to feel like I am editing a movie.

“It may cost more to use a desk and outboard, but you can’t cheapskate good work. In my experience, when you are sitting in front of a computer, you’re missing out on something. Honestly, when you are looking at a screen, you are looking at numbers. Whereas when you are on a board in analogue, you are working with your ears. In digital you can turn things up or down a specific amount of decibels, or tune this or that frequency. But how useful is that? It is a bit like going to a school for engineering. You can learn many valuable things there, but the one thing that you cannot be taught is how to hear something. Nobody else can teach you your own taste and tell you what number is right. It is just a number. Instead you have to train your ear, you have to learn to notice the different frequencies and sounds, and then let your own taste decide.”

Tom-Tom Club

Kendrick Lamar is, by all accounts, a workaholic, who loves nothing more than spending time in the studio writing and recording. And so work on To Pimp A Butterfly began at the end of 2012, immediately after the release of and promotional tour for M.A.A.D City. Lamar and Ali spent most of their time at No Excuses in LA, with the other studios mentioned in the credits for the album used only very briefly.

“Sometimes Kendrick would do a show somewhere, and after the show he still wants to work, so we go to a local studio,” recalls Ali. “He’s also had a studio in his tour bus ever since we were on tour for the first album. If he didn’t have that, he’d be recording in GarageBand! So we made it easier for him, and set up this studio in the bus, with a simple setup, consisting of a Pro Tools HD rack, two mics, the Sony C800G and a Telefunken U47 and an Avalon mic pre. Nothing crazy, just stuff that allows us to get down ideas. But our main headquarters for the making of the album was Tom-Tom (the nickname for No Excuses Studio), which is owned by Interscope. It has Dre’s former SSL 4000 G+, the last G-series ever built, in 1991. He mixed his album The Chronic (1992) on it and Eminem’s The Slim Shady LP (1999), and lots of other famous albums, so it’s a real classic board in rap history.”

Far more live musicians and fewer samples were used than is normal on a hip-hop album. “The main guys who were there for the entire making of the album were Kendrick, myself and producers Terrace Martin, Rahki, Tae Beast and Sounwave [the latter two are members of the Digi+Phonics production collective, the main in-house producers for TDE]. That was the core personnel, and we were involved from day one until the day we finished the last mix. We consider each other brothers, and Kendrick does not look at this as purely his album. When we were in the studio he talked about it as our album. He brought everybody in and we voted on how things should sound and work. When we played what we were doing to people, many were just dumbfounded and said that they’d never heard anything like this before. For this reason the other producers had to be around and feel the energy and connect with Kendrick’s vision.

“The other producers came in when Kendrick had ideas for working with them, guys like Pharrell, Thundercat and Flying Lotus. Boi-1da is based in Toronto and he was one of the only ones who didn’t come over to the studio. The general working method in hip-hop of the producer sending over some beats didn’t work for this album. There were just a couple of songs on the album that came out of people sending us beats. Like Kendrick found this beat by Knxwledge in his e-mail, and we were like, ‘What’s this?’ It just matched the aesthetic of the album so well, and we used it for the track ‘Momma’. But A&R guys sometimes brought in producers or tracks and we’d just be sitting there looking at each other and going, ‘This has nothing to do with what we’re doing at the moment.’”

Writing In The Head

Although Dr Dre is credited as the executive producer of To Pimp A Butterfly, Ali stresses that it was Lamar’s vision that unified all the album’s disparate ingredients and contributors. “It’s almost crazy watching him, because he knows exactly what he wants. Big names mean nothing to him. He may listen to the way someone sings or plays, and if he likes it, he’ll incorporate that into his project, but in a way that fits his vision. He looks at people’s vocals as instruments. Kendrick knew what he wanted to talk about with regards to the lyrics, and from there it was a matter of piecing the music together, and making that fit with the vocals. He writes in his head, and he’ll hear a beat, or a bass line, or an instrumental or vocal melody, and he’ll build a track from there. Like Thundercat may be playing an amazing bass line in the studio lounge, and Kendrick might be having a conversation with someone else, but a moment later he’ll write something to fit that bass line, and five minutes later he’ll say, ‘Let’s record that.’ With the track ‘i’ he was literally trying to play a guitar to demonstrate what he wanted. He writes all the words, of course, but is also 100 percent involved in the writing of the music.

“We recorded 60 to 80 tracks for this album over the three years, and Kendrick tried many different concepts and approaches. The final direction began to emerge in the last year and a half or so, with most of the tracks written and played from the ground up. There were many live instruments used, and that’s why we had our core team, with guys programming drums, and playing bass, guitars and keyboards, so we could arrange the music in the studio, live. Most songs would start with drums and bass, over which Kendrick would record a rough vocal. After that we’d stack the rest of the musical instruments on top, usually layer by layer. He tends to mumble melodies or harmonies for his roughs on top of the drums and bass, and after we recorded all the music, he’d write the actual lyrics and then he’d record his vocals again. It was kind of a backwards way of working, but it was cool.”

In addition to programmed drums and electronics, the album also features acoustic instruments like violin, trumpet, guitar, double bass, saxophones, clarinet, organ, piano, as well as extensive backing vocals. “Each song had its own sound world and its own process,” explains Ali. “The opening track, ‘Wesley’s Theory’, initially did not have the Boris Gardiner sample, but was produced by Flying Lotus, with Sounwave doing the instruments. ‘King Kunta’ is bass-heavy and influenced by the West Coast hip-hop from DJ Quik, who was big in the gangsta movement of the ’90s, and who had loads of jazz and funk influences in his music. Kendrick really wanted his sound for this song, and he had started with doing a vocal to a beat by DJ Quik. Sounwave then later created a new beat to match Kendrick’s vocals.

“‘For Free?’ was produced by Terrace Martin, who is a jazz player himself, and who arranged the song for a live jazz band. The energy of that session was amazing. I had never seen anything like that ever in my life. It got me into jazz, honestly. Just tuning my ears for his album I’ve been listening to a lot of jazz albums, and I kind of fell in love with it. In fact, this album opened my ears to many different genres of music. I come from a place where there was no jazz; I was raised on gangsta rap.”

All About Feeling

As the main engineer on To Pimp A Butterfly, Ali was responsible for keeping track of everything and organising the material, with the assistance of James Hunt and Matt Schaeffer. According to Ali, he and Lamar work in a very collaborative way, with the artist relying on Ali to supply him with sonic ideas that he then uses for inspiration.

“With Kendrick it’s all about feeling. If it doesn’t feel good, it’s not going to work for him. And what a lot of people don’t realise is that you can alter people’s emotions with certain frequencies and sonic textures. The fact that I can add delays and reverbs and other crazy effects to music or vocals and give them extra emotion is amazing to me. That’s what I do this for. Kendrick understands this, and he may be midway through recording a verse, and he’ll then ask me to try something, like ‘Can you add some flanging, or some panning, or something else crazy?’

“We’ve been working like that for years and it got my ears tuned to all kinds of different effects. When it’s during recording, I tend to do these effects in the box. It might take me a few minutes to set up, but it’s fun. In some ways the engineer-artist relationship is like driving a car, going on a road trip. The artist knows where he wants to go, but it is up to the engineer to take him there.

“The whole recording process was like filling in a check-sheet, and Kendrick always knew what he still had to finish or go back to. Towards the end of the project it became more of a mix-as-you-go situation, because of deadlines, but in general, once all the parts were recorded, and the song was structured and edited and sequenced, it was time to mix. Kendrick and I would have already discussed the direction for each song during the recordings, so for me also it’s just a matter of waiting until all the sounds are in, piecing and editing everything together in Pro Tools, and then I’d wait a day, to give my ears a break, and then it was time to do the final mix.

“We did all the mixes at Tom-Tom. The process was that after my day off I’d lay the mix out over the SSL, and then I’d spend one or two days on the mix. Kendrick and the other guys would be present with me in the room while I was mixing, non-stop. I am blessed to work with them, because they give me freedom to do all this crazy stuff, because they know what I am capable of. They’re not leaning over my back telling me what to do. After the initial one or two days mixing, I’d spend a day living with the mix, listening to it on all sorts of different speakers and in different situations. I’ll listen in my car, on my little home boombox speaker, in all sorts of places where people will be hearing them. Kendrick and I might also be listening to it in my home studio, where I have a Pro Tools rig, and Yamaha NS10s, Neumann and Auratone monitors. We’ll discuss what elements we want to bring out more. But really, most of the mix is done after those first one or two days. After that it’s just a matter of adding a little bit of sugar and spice. I’d come back in the studio the next day, and incorporate any final feedback from the guys, and I’d then print the mix, back to Pro Tools via a Lavry Gold A-D converter, and to half-inch analogue tape, using an Ampex ATR102 machine.”

home page

Only registered users can see Download Links. Please or login.

No comments yet